Today I'll share a review for Ward No. 6 (Палата № 6) a short story by Anton Chekhov. First published in 1892, this story is still relevant. It criticizes society (especially its treatment of mentally ill) through observing one doctor's existential crisis. While telling a story of one doctor's burnout, Ward No.6 opens many interesting questions about human suffering and the meaning of life. While I was in Split, I stumbled across an Italian edition of this story in a that antique/second hand bookshop I told you about, so I bought it. Short stories are a great choice whenever you're pressed for time.

I have already read this story in Croatian a couple of times. Possibly I had also listened to some of the Russian audio-versions on YouTube at some point, but I'm not certain. I'm actually listening to the above mentioned and linked audiobook while I'm putting this post together, just to refresh my memory. You can read this short story in English for free on project Gutenberg or download it to your Kindle. You can also read the whole story on wikisource (that's where I got the quotes I'll use in my review from). I own two editions with Chekhov's short stories, both including this Ward No.6 story. The reason why I bought the Italian edition is simply to refresh my Italian language skills a bit. My Italian was never at a very high level and I'm getting rusty because I don't use it often enough. Reading in foreign languages is a good way to refresh one's language skills, at least that is what I found. I must admit that I didn't finish this story in Italian, because I misplaced this particular book somewhere, but I did read it many times.

A long time ago, someone asked me how I can read the same book twice. I hadn't a reply to that question then- but I could answer it now or rather- form a reply in a form of a question. How can you listen twice to the same song? It's the same with books. A short story is a shorter form of literature, just like a song is musical composition in its short form. Shorter or longer, it doesn't matter, the analogy stands. People listen to compositions that are hours long over and over again and rewatch long movies. So, what is strange about reading the same book twice? Art is art, it can be enjoyed as you see fit. If you love books as much as you love music or film, you will be able to read them not only twice but an infinite number of times. That's my experience anyway.

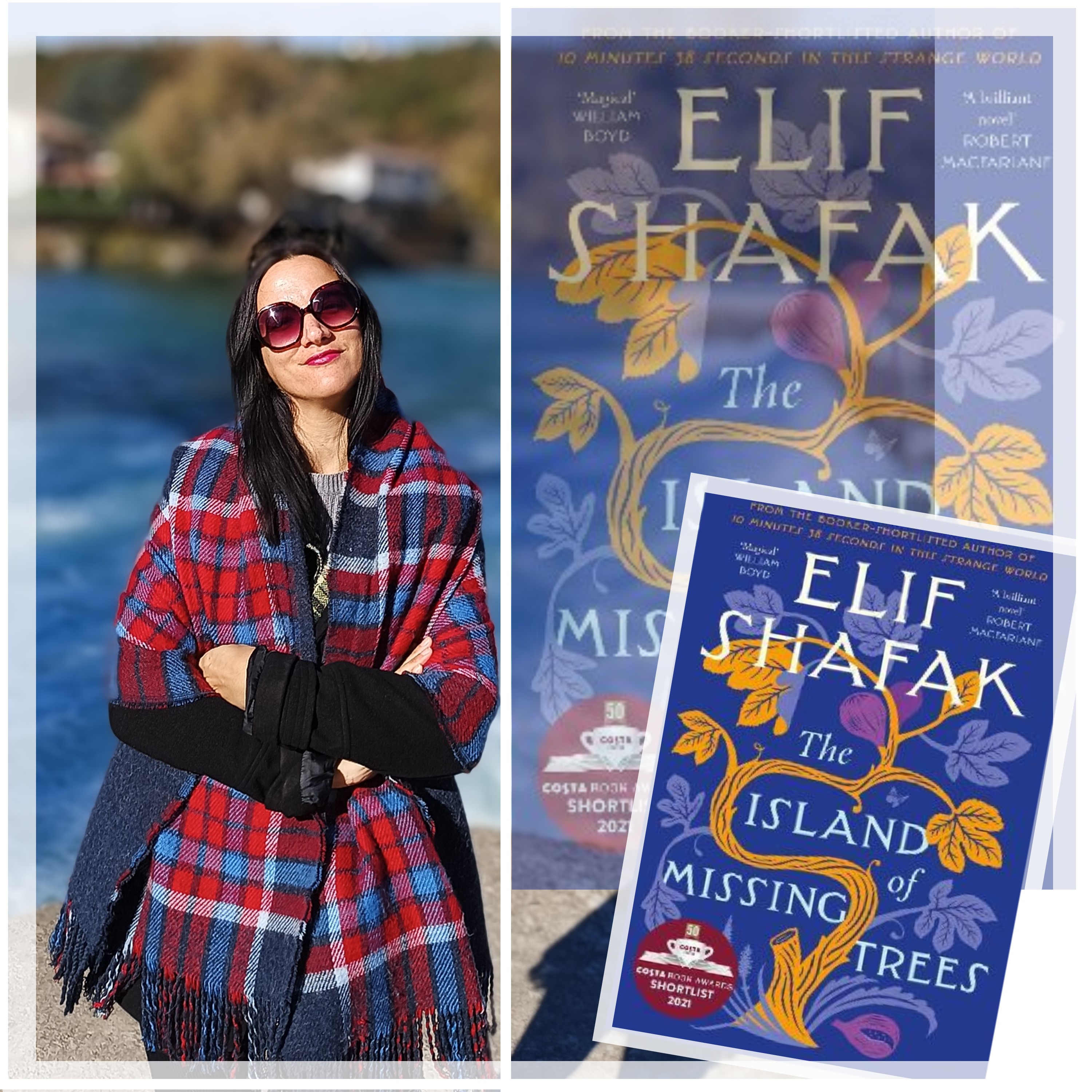

I don't see a difference between listening to a song (or an album) on repeat, rewatching a movie or rereading a book multiple times. If I really like a book, I might read it a number of times or even periodically (every few years). That's especially the case with my favourite authors and Anton Chekhov is one of my personal favourites. You can read my reviews of some of his works published previously on my blog.I have previously reviewed some of his his stories ( The Wife, The Living Chattel), one of his dramas (The Three Sisters), and his novel (Three Years).

* Prijevod objave na hrvatski u tijeku.

WARD NO.6, A SHORT STORY BY ANTON CHEKHOV

This story opens with a description of a hospital, focusing on the part of the hospital where the mentally ill are placed. With little words, Chekhov paints the scene in perfect detail. You can really tell that he is the master of short form when you read those initial descriptions. His writing is descriptive and economical, but still soulful and with enough details for you as reader to create a vivid picture in your mind: " In the hospital yard there stands a small lodge surrounded by a perfect forest of burdocks, nettles, and wild hemp. Its roof is rusty, the chimney is tumbling down, the steps at the front-door are rotting away and overgrown with grass, and there are only traces left of the stucco. The front of the lodge faces the hospital; at the back it looks out into the open country, from which it is separated by the grey hospital fence with nails on it. These nails, with their points upwards, and the fence, and the lodge itself, have that peculiar, desolate, God-forsaken look which is only found in our hospital and prison buildings...."

Very soon into the story, we get to know about the staff and the patients in Ward number 6. The conditions they live in are rather dreadful. Nikita, the guard at ward no.6, often beats the patients, believing that is a just thing to do:

...The porter, Nikita, an old soldier wearing rusty good-conduct stripes, is always lying on the litter with a pipe between his teeth. He has a grim, surly, battered-looking face, overhanging eyebrows which give him the expression of a sheep-dog of the steppes, and a red nose; he is short and looks thin and scraggy, but he is of imposing deportment and his fists are vigorous. He belongs to the class of simple-hearted, practical, and dull-witted people, prompt in carrying out orders, who like discipline better than anything in the world, and so are convinced that it is their duty to beat people. He showers blows on the face, on the chest, on the back, on whatever comes first, and is convinced that there would be no order in the place if he did not."

Among the five mentally ill patients, one stands out. Ivan D. Gromkov, an educated and sensitive man who suffers from mania of persecution. The writer tells us of his past. Ivan was well liked in the town for his gentle manners and respected for his education. Ivan speaks about women with respect bordering on adoration, but he himself has never been in love. However, his paranoia got too strong so Ivan ended up in the hospital. Certainly, it was hard not to sympathize with such a man, someone who wouldn't hurt a fly and is kind to everyone: "Ivan Dmitritch Gromov, a man of thirty-three, who is a gentleman by birth, and has been a court usher and provincial secretary, suffers from the mania of persecution. He either lies curled up in bed, or walks from corner to corner as though for exercise; he very rarely sits down. He is always excited, agitated, and overwrought by a sort of vague, undefined expectation. The faintest rustle in the entry or shout in the yard is enough to make him raise his head and begin listening: whether they are coming for him, whether they are looking for him. And at such times his face expresses the utmost uneasiness and repulsion.

I like his broad face with its high cheek-bones, always pale and unhappy, and reflecting, as though in a mirror, a soul tormented by conflict and long-continued terror. His grimaces are strange and abnormal, but the delicate lines traced on his face by profound, genuine suffering show intelligence and sense, and there is a warm and healthy light in his eyes. I like the man himself, courteous, anxious to be of use, and extraordinarily gentle to everyone except Nikita. When anyone drops a button or a spoon, he jumps up from his bed quickly and picks it up; every day he says good-morning to his companions, and when he goes to bed he wishes them good-night."

A doctor is introduced into the story. Andrey Y. Ragin never cared for natural sciences, but life circumstances directed him toward the medicine. The hospital Andrey finds himself in this story is poorly supplied. So poorly supplied and not functional, that the doctor is sure that the best thing to do is to discharge everyone's from it and let nature take its course. Still, doctor Andrey understand that this is impossible. If people put up with such a hospital, than that is what they can (or need to) put up with. Such a hospital is necessary to them- and besides they don't have another one. Andrey realizes there's little he can do to stop the never ending flow of patients. You cure thirty patients today, tomorrow there are thirty five. At first the doctor does what he cans, but soon he (as we would say in our modern times) experiences burn-out:

"At first Andrey Yefimitch worked very zealously. He saw patients every day from morning till dinner-time, performed operations, and even attended confinements. The ladies said of him that he was attentive and clever at diagnosing diseases, especially those of women and children. But in process of time the work unmistakably wearied him by its monotony and obvious uselessness. To-day one sees thirty patients, and to-morrow they have increased to thirty-five, the next day forty, and so on from day to day, from year to year, while the mortality in the town did not decrease and the patients did not leave off coming. To be any real help to forty patients between morning and dinner was not physically possible, so it could but lead to deception. If twelve thousand patients were seen in a year it meant, if one looked at it simply, that twelve thousand men were deceived. To put those who were seriously ill into wards, and to treat them according to the principles of science, was impossible, too, because though there were principles there was no science; if he were to put aside philosophy and pedantically follow the rules as other doctors did, the things above all necessary were cleanliness and ventilation instead of dirt, wholesome nourishment instead of broth made of stinking, sour cabbage, and good assistants instead of thieves; and, indeed, why hinder people dying if death is the normal and legitimate end of everyone? ...."

I could imagine the everyday toil it took on the doctor, especially working in such poor conditions. So, Andrey becomes emotionally numbed and it is no wonder. He is not a strong willed man, he doesn't find it easy to give orders and besides he doesn't have any allies in the hospital. When other hospital staff steals or does something dishonest, Andrei doesn't shout at them but accepts it as it is. Andrey soon becomes overwhelmed with his responsibilities. Moreover, Andrey doesn't know how to help his patients who complain of hunger and bad conditions of life. Their complaints confuse him and make him feel guilty- even if obviously he is no way guilty for the existence of the poor.

Andrey is in essence a good man who gives up doing good because he's overwhelmed seeing suffering everywhere. However, sometimes being a good man isn't enough to make things better. The harsh reality of hospital life presses on him, so Andrey becomes more withdrawn. I found it easy to sympathize with him, to imagine the every day flow of work that start starts to feel meaningless. You could say that Andrei does (or feels like he does) the Sisypus' work. On his own, Andrey cannot improve the hospital or the conditions of most of the patients. Andrey cannot cure them of being poor and hungry. At start, people thought well of Andrei for he proved useful at diagnosing health conditions, especially when it came to women and children. However, as he descents into pessimism, Andrey himself starts to work less, avoiding his medical duties that now seem futile to him. Andrey lets the hospital stay in its chaotic state and allows his (corrupt) assistant to take over his duties: "Andrey Yefimitch never performed any operation when he was seeing patients; he had long ago given up doing so, and the sight of blood upset him. When he had to open a child's mouth in order to look at its throat, and the child cried and tried to defend itself with its little hands, the noise in his ears made his head go round and brought tears to his eyes. He would make haste to prescribe a drug, and motion to the woman to take the child away. He was soon wearied by the timidity of the patients and their incoherence, by the proximity of the pious Sergey Sergeyitch, by the portraits on the walls, and by his own questions which he had asked over and over again for twenty years. And he would go away after seeing five or six patients. The rest would be seen by his assistant in his absence."

One day Andrey wonders into Ward No.6 where he starts a conversation with patient Ivan, an intelligent man, who in a moment of clarity, wants to know why he is being kept there and offers good arguments against it.

""What are you keeping me here for?"

"Because you are ill."

"Yes, I am ill. But you know dozens, hundreds of madmen are walking about in freedom because your ignorance is incapable of distinguishing them from the sane. Why am I and these poor wretches to be shut up here like scapegoats for all the rest? You, your assistant, the superintendent, and all your hospital rabble, are immeasurably inferior to every one of us morally; why then are we shut up and you not? Where's the logic of it?"

"Morality and logic don't come in, it all depends on chance. If anyone is shut up he has to stay, and if anyone is not shut up he can walk about, that's all. There is neither morality nor logic in my being a doctor and your being a mental patient, there is nothing but idle chance."

Doctor Andrey starts to visit Ivan, not as a patient suffering from paranoia, but as an intelligent man he can converse with. Doctor Andrey has been hungry for intellectual conversation. Soon doctor Andrey comes to enjoy their cultivated and philosophical conversations. However, soon the doctor is suspected by others. The people in the hospital suspect that Andrey too must be mad. For why would anyone choose to talk with a mad man on daily basis? They could understand if he did it one or twice, out of curiosity but not the regularly of his visits. His corrupt assistant who has a private clinic is anxious to get rid of the doctor and take over all the patients, so the assistant starts to add to rumors about Andrey's insanity.

"After this Andrey Yefimitch began to notice a mysterious air in all around him. The attendants, the nurses, and the patients looked at him inquisitively when they met him, and then whispered together. The superintendent's little daughter Masha, whom he liked to meet in the hospital garden, for some reason ran away from him now when he went up with a smile to stroke her on the head. The postmaster no longer said, "Perfectly true," as he listened to him, but in unaccountable confusion muttered, "Yes, yes, yes . . ." and looked at him with a grieved and thoughtful expression; for some reason he took to advising his friend to give up vodka and beer, but as a man of delicate feeling he did not say this directly, but hinted it, telling him first about the commanding officer of his battalion, an excellent man, and then about the priest of the regiment, a capital fellow, both of whom drank and fell ill, but on giving up drinking completely regained their health. On two or three occasions Andrey Yefimitch was visited by his colleague Hobotov, who also advised him to give up spirituous liquors, and for no apparent reason recommended him to take bromide. "* (all quotes taken from the original text available on wikisource)

This is a simple story in terms of the plot, but written so well, it becomes a profound one. The philosophical conversations between the doctor (Andrey) and the patient (Ivan) are so well written. I remember the profound sorrow I felt the first time I have read it. Somehow this short story sums up all the life's tragedies for me. It's a very human story with a very human protagonist. Surely, doctor Andrey is guilty for not trying to improve the conditions of the hospital and for avoiding his duties as a doctor, but how can we judge him? Andrey is a sensitive person, a man who avoids all confrontation, not only out of cowardice or laziness but because he actually cares about other human beings and hates to see them suffer. Seeing human beings in distress makes this doctor ill at times, such is his sensibility. However, this avoidance of confrontational leads Andrey to ignore his duties- and this is his tragic flaw. Similarly, Ivan falls victim to his paranoia, that is perhaps increased by his sensitivity and intelligence. Anton Chekhov gives a phenomenal psychological portrayal of two sensitive and intelligent men, both out of place in society. Ward No.6 is perhaps the most melancholic and pessimistic of all Chekhov's short stories, but is on of my personal favourites. It's absolutely brilliant! I highly recommend reading it.

OUTFIT DETAILS- THE STORY OF MY OUTFIT- HOW I WORE THESE ITEMS BEFORE?

THE DENIM SKIRT WITH DIY PATCHES (no name)-

here ,

here &

here

LOCATION:

ŽNJAN & DUILOVO BEACH

SPLIT, CROATIA

I took these photographs last October, while I was still in Split, Croatia. As is pretty evident from the photographs, this was a comfy styling I wore for a walk by the sea. I had a nice time in company of waves and Chekhov's prose. You've to hold on those precious happy moments sometimes.

Thank you for reading. Have a nice day!

It's a shame you misplaced this book but good you know the ending as you've read it before :) I like to re-read books as well! I can only read and talk in English though, haha! I am not as good with languages as you are.

ReplyDeleteHope that you are having a good week :) Yet another rainy spring day here!

Away From The Blue

Thanks dear. I have this story in several book editions so I can always take it up. Plus, it is available online.

DeleteParece un buen libro es uyna pena cuando perdemos un libro. Lindo look , Te mando un beso

ReplyDeletegracias

DeleteSuch poetry in the language! It reminds me a bit of Nabokov - I have only read a couple of short stories by Chekov, but your review makes me want to seek him out. Thanks, Ivana!

ReplyDeleteI used to reread books more than I do now - now, I find that there are just too many books I want to read, and not enough time to reread old favourites. However, Ray Bradbury is an author I go back to, over and over.

I caught my breath with that first picture of the ocean - so green, so beautiful! Hope you are doing well, my friend.

Yes, the language is simple but very poetical none the less- I can see why it makes you think of Nabokov.

Delete❤️

ReplyDelete<3

DeleteThe book sounds really good and I like reading old books like this one, they offer a different perspective. I haven't heard of it before, but I will check to see if I can find it at the library. xx

ReplyDeleteThanks dear:)

DeleteThanks for your review:)

ReplyDelete<3

DeleteI love that atmospheric photo at the end.

ReplyDeleteLike Sheila say, I love the poetry of Russian literature. I had a passion for it as a teenager but haven't read any as an adult. xxx

I started reading and enjoying it as a teenager too, but I got back to it. :)

DeleteThose are amazing photos :-D

ReplyDeleteThanks, I don't often take my own photos.

DeleteIf I'm honest, I don't think I've ever read any Chekhov. His short stories are probably the best way to start, so thank you for recommending this. As for re-reading books, I used to do that when I was much younger. Lately, not so much, although I am still holding on to books for that very reason. That final photo is stunning. There's nothing like a walk by the sea to reconcile oneself with the world at large. xxx

ReplyDeleteYes, a walk by the sea is always a blessing.

DeleteAnton Chekhov's books are popular here such as "The shooting party". But i havent read any book from this writer. Thanks for the review.

ReplyDelete<3

DeleteLeggere apre cuore e mente

ReplyDeletesi, bel detto cara.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteGreat post and beautiful pictures

ReplyDeletethanks

DeleteHello again Ivana,

ReplyDeleteOooh this is so good because I have a lot of books with shorts stories by Checkhov, I haven't read all of them but maybe this story is probably included in one of these titles that are in my library! I'll let you know.

On the other side I liked the design of the cover and the way you took us to the melancholia of Chekhov by connecting his stories to these pictures in blue shades.

Pablo

www.HeyFungi.com

<3

DeleteIt looks like you had a nice day by the seaside when you took these photos. This book sounds like a compelling read and very much in line with Anton Chekov's works in general which are known to be deeply drawn and beautifully written though often quite bleak.

ReplyDelete<3

DeleteYour review definitely makes me want to read the story. It sounds very beautiful. I also love the photos you shared. You're right that it's important to treasure good memories.

ReplyDeleteI also loved your comparison of books to music. You're right that they are all art and I'm always surprised when people don't think of writing as such.

Ekaterina | Polar Bear Style

Thank you!

Delete