Just a few sentences into the story, we don't know much about the men and their quest or their leader Bela. Still, with the mention of slavery and indication that the guide guiding them grew up as slave, despite being brother-in-law of Bela's brother, we might conclude that these men might be looking for nomad people for sinister motives. As a reader, it's fairly easy to connect the dots so far, and conclude this men might be hunting for nomad people. Moreover, we're soon to find out more about Bela, his men and the guide.

What happens next is something that gives a good indication of what slave owning society is really like- horrible in its mistrust. How can you ever trust someone you enslaved? How can a slave ever trust the person who enslave him? There's no way, so this basically means that any slave owning society must be a society of mistrust and fear, rotten and corrupted at its core. I found that this detail was a good foreshadowing. At this moment in the story, we don't really know much about this society, but this moment of mistrust tells us a lot as readers.

The guide acts surprised, and whether that is what he really feels, we are not yet to know. However, as the guide gives arguments, we learn more about the organization of this slave owning society. From his speech, we can conclude that the guide men doesn't want to return to nomad people. Has he forgotten what freedom is? Or is he bound by the fact his sister is married to this family? Is be bound by his sister's fate, his sister possibly being the only family the guide had left?

The arguments that the guide gives make sense. His sister is married to Bela's brother, they share a nephew, and they are in a way- a family of sorts. Nevertheless, the mistrust is there. I think Le Guin left his monologue unanswered to indicate that. Where there's slavery, there can be no trust, no friendship and no family in the true sense of the word.

Fear is a part of the story now, and it will be a part of the story until the end. I feel that Le Guin did this on purpose, to show the full extent of the evil of slavery. It makes everything a lie. Slavery robs dignity from both the slave, and the slave owner.

Le Guin uses adjective young to describe these men. We can imagine how they feel. Afraid and in unknown land, tired from everything. No wonder they fall asleep, allowing for Bidh's escape.

I think this story really puts forward an idea that a slave owner is also a slave of the society he lives in. It's a rotten system for everyone, not allowing for any freedom. The owners have to fight to remain owners, and the slaves have to fight to break free. In the end, nobody is truly free.

I feel the message of this story is that ultimately there's no freedom for anyone in a slave owning society. The way this story progresses is quick, and soon we're taken aback by the events described. Bel and his men take their arms against women, children and a few old men. This is certainly something detestable, yet these men can justify their actions by saying that is just how their society is organized.

I think it's important to remember, especially with stories dealing with this topic, is that slavery still exists. If anything there are more slaves today then ever witnessed in human history. If we're to fight against slavery, we need to realize that slavery is something that had not only accompanied human kind since the dawn the time, but it's something that human kind falls into by default. We need to understand there might be something inheritably wrong with how our societies are organized. If we are to abolish slavery, we need more than activism, we need fundamental change of human society.

I'm getting a bit philosophical now, but stories like this one are meant to be read seriously. Not every story, novel or novella is about an engaging plot or characters. Sometimes the message told is what the most important thing is. Some stories need to be studied for what they are- a profound works of literature.

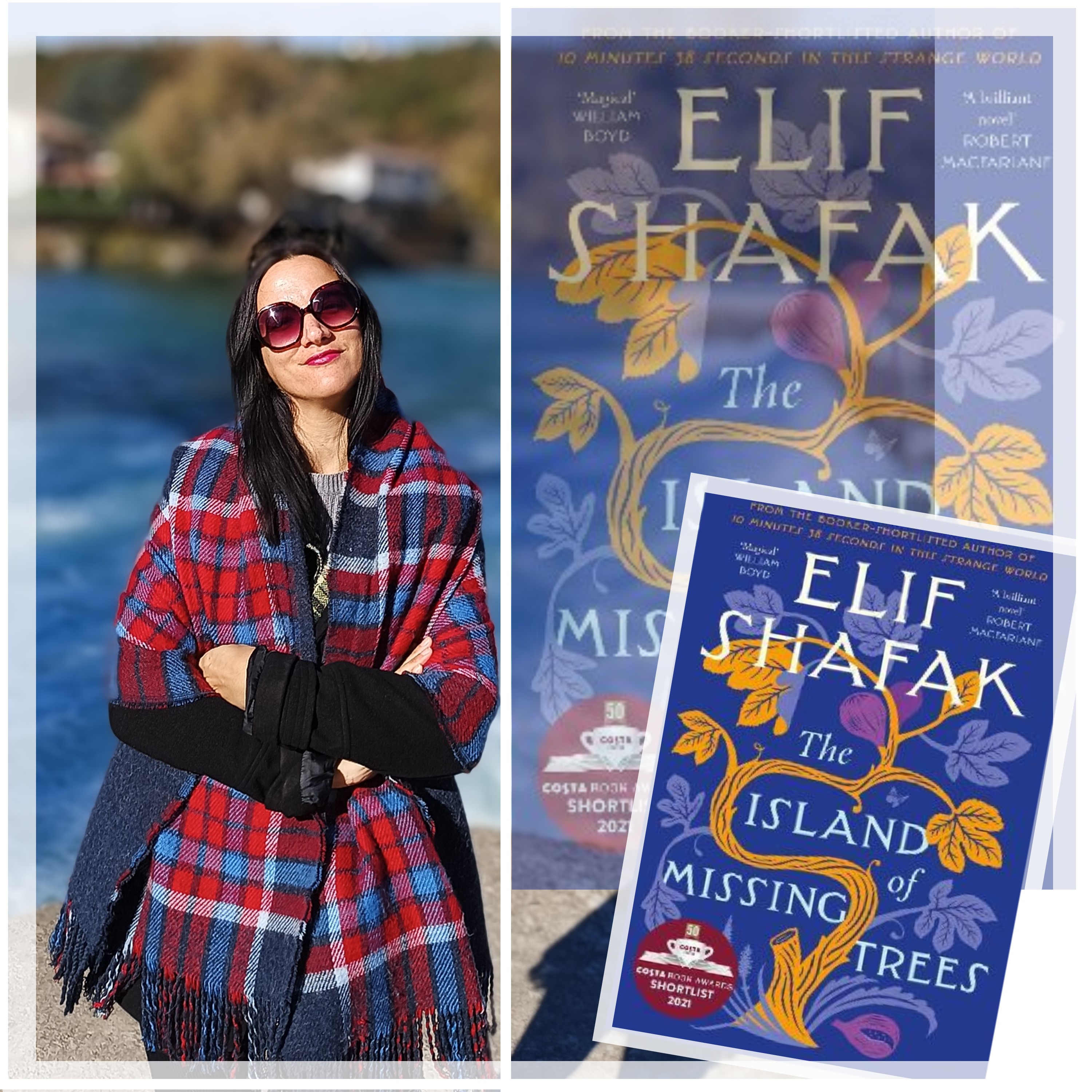

More than anything else, this passage made me think of one book I reviewed in 2016-

While I'm mentioning this book, there's another deeply impactful science fiction story that focuses on the theme of slavery. In 2023, I reviewed another science fiction short story by Robert A. Heinlein: 'Logic of Empire'. You may read 'Logic of Empire' here. Among his shorter prose, this story remains one of my favourite ones. First published in 1941 in Astonishing Science Fiction, 'Logic of Empire' is a realistic depiction of future slavery. It is a story set in future, a chilling tale of two men who are sold to slavery on Venus.

When it comes to literary accounts of slavery, one must mention Beloved by Toni Morrison. Beloved was a novel that absolutely broke my heart when I read it back in Uni. Since then, I've read a number of books by Toni Morrison. I'd like to recommend not just Beloved, but her whole trilogy about slavery.

Paradise was my second novel by Toni Morrison. Prior to it, I had read Beloved. I had read Beloved as a student. When I started reading Paradise, I was expecting another Beloved but I couldn't have been more wrong. Having read three of her novels so far ( Beloved, Paradise and Jazz) , I can state that every one of them is remarkably unique. All of Morrison's novels that I have read so far explore similar subjects, but there is no repetition. Morrison’s novels are all superb masterpieces with an amazing set of characters and masterful narrative. All of her novels have great psychological and emotional depth. NOW, LET'S BACK TO REVIEWING THIS STORY

Now, that I have shared writing that I feel is relevant for understanding of this story. Certainly, it's relevant for the impact that this story had on me, because reading all of those books made this story seem so important to me. While reading it, I was not focused only on the story and the characters, I was also very conscious of the social and philosophical message that could be a part of the writing.

URSULA K LE GUIN DOESN'T HOLD BACK WHEN DESCRIBING THE TRAGEDY

As I said, the language used to describe what is essentially a massacre of the nomad people is simple enough, but that makes it all the harder to read. It's easy to imagine the chaos, the violence and the shock. Bela and his friends don't really know what they are doing, and may act even more violent because of all that. It becomes clear that Bela and his company ventured into all this without any plans. As the story unfolds, we learn more about the organization of society. The men's motivation is to get potential wives, and apparently they plan to wait for the girls they kidnap to grow up so they can marry them. Do all men in the city marry slaves? How does this society exactly works? Are the women freed once they are wives?

Young men on their first foray, the soldiers had made no plans—Bela ten

Belen had said to them, “I want to go out there and kill some thieves and

bring home slaves,” and that was all the plan they wanted. To his friend Dos

ten Han he had said, “I want to get some new Dirt girls, there’s not one in the

City I can stand to look at.” Dos ten Han knew he was thinking about the

beautiful nomad-born woman his brother had married. All the young Crown

men thought about Nata Belenda and wished they had her or a girl as

beautiful as her.

THE SCENE WE WITNESS AS READERS AS CHILDREN ARE ABDUCTED IS NOT EASY TO READ

Some of the older children manage to flee, but the younger ones are doomed, as they are easily captured. In the chaos, Bela even kills one of the children to silence them. Not an easy read!

“Get the girls,” Bela shouted to the others, and they all ran at the

children, seizing one or another. The older children had mostly fled at once, it

was the young ones who stood staring or began too late to run. Each soldier

caught one or two and dragged them back to the center of the village where

the old men and women lay in their blood in the sunlight.

NOW THE HUNTERS TURN INTO PRAY

Some of the older children managed to escape and call their parents, so now Bela and his men turn from hunters into hunted and flee with the few children they kidnapped.

“Follow the river back,” Bela said, snatching up a girl of about five years

old. He seized her wrists and slung her on his back as if she were a sack. The

other men followed him, each with a child, two of them babies a year or two

old.

The raid had occurred so quickly that they had a long lead on the nomads

who came straggling up round the hill following the children who had run to

them. The soldiers were able to get down into the rivercourse, where the

banks and reeds hid them from people looking for them even from the top of

the island.

The nomads scattered out through the reedbeds and meadows west of the

island, looking to catch them on their way back to the City. But Bela had led

them not west but down a branch of the river that led off southeast. They

trotted and ran and walked as best they could in the water and mud and rocks

of the riverbed. At first they heard voices far behind them. The heat and light

of the sun filled the world. The air above the reeds was thick with stinging

insects. Their eyes soon swelled almost closed with bites and burned with salt

sweat. Crown men, unused to carrying burdens, they found the children

heavy, even the little ones. They struggled to go fast but went slower and

slower along the winding channels of the water, listening for the nomads

behind them. When a child made any noise, the soldiers slapped or shook it

till it was still. The girl Bela ten Belen carried hung like a stone on his back

and never made any sound.

THE SISTERS ARE REUNINTES AS ONE CHILD GIVES UP HER FREEDOM SO THE OTHER ISN'T ALOVE

Soon the men hear a noise and raise their swords, but it turns out that they were followed by a child. A girl or eight or nine has followed them because Bela had taken her sister. The men realize that she presents no danger to them.

Dos ten Han pointed northward: he had heard a sound, a rustling in the

grasses, not far away.

They heard the sound again. They unsheathed their swords as silently as

they could.

Where they were looking, kneeling, straining to see through the high

grass without revealing themselves, suddenly a ball of faint light rose up and

wavered in the air above the grasses, fading and brightening. They heard a

voice, shrill and faint, singing. The hair stood up on their heads and arms as

they stared at the bobbing blur of light and heard the meaningless words of

the song.

The child that Bela had carried suddenly called out a word. The oldest, a

thin girl of eight or so who had been a heavy burden to Dos ten Han, hissed at

her and tried to make her be still, but the younger child called out again, and

an answer came.

Singing, talking, and babbling shrilly, the voice came nearer. The marsh

fire faded and burned again. The grasses rustled and shook so much that the

men, gripping their swords, looked for a whole group of people, but only one

head appeared among the grasses. A single child came walking towards them.

She kept talking, stamping, waving her hands so that they would know she

was not trying to surprise them. The soldiers stared at her, holding their heavy

swords.

She looked to be nine or ten years old. She came closer....

ONE OF THE CHILDREN DIES AS A RESULT OF THE RAID AND IS NOT BURRIED

This is an incident that's important on more than one level. The sisters believe that if the body remains unburied it will come to haunt them. This happens, and it's up to the reader to decide whether that part of the story is fantastical or not.

THE GUIDE BIDH RETURNS TO BELA, EXPLAINING THAT HE ONLY WANTED TO WARN HIS PEOPLE

The guide Bidh is the perfect example of the complexity of the situation. He loves his people, and wants to preserve them. At the same time, the men treating him are also his family, for his sister is married to one of them and is adored as a goddess. As incredible as it seems, Bidh and Bela are a kind of family, even if the meaning of the word itself gets twisted by slavery.

“But you ran away!”

“I wanted to see my family,” Bidh said.

“And I didn’t want them to be

killed. I only would have shouted to them to warn them. But you tied my legs.

That made me so sad. You failed to trust me. I could think only about my

people, and so I ran away. I am sorry, my lord.”

“You would have warned them. They would have killed us!”

“Yes,” Bidh said, “if you’d gone there. But if you’d let me guide you, I

would have taken you to the Bustu or the Tullu village and helped you catch

children. Those are not my people. I was born an Allulu and am a man of the

City. My sister’s child is a god. I am to be trusted.”

Bela ten Belen turned away and said nothing.

He saw the starlight in the eyes of a child, her head raised a little,

watching and listening. It was the marsh-fire girl, Modh, who had followed

them to be with her sister.

“That one,” Bidh said. “That one, too, will mother gods.”

BIDH ADVISES THE SISTER CHILDREN AND EXPLAINS THE SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Bidh talks with the captured sisters. He explains that men of the city can only marry Dirt people (that is captured slaves). If they manage to became wives, the girls won't be slaves anymore, they will live a privileged life in some ways. Still, it's unclear how much freedom they will really have as the wives of men at the top of the social hierarchy.

The little sister, Mal, was awake, listening. Modh put her arm around her

and whispered, “Go back to sleep.”

Near them, Bidh suddenly sat up, scratching his head. The girls stared

wide-eyed at him.

“Well, Daughters of Tullu,” he said in their language, spoken the way the

Allulu spoke it, “you’re Dirt people now.”

They stared and said nothing.

“You’re going to live in heaven on earth,” he said. “A lot of food. Big,

rich huts to live in. And you don’t have to carry your house around on your

back across the world! You’ll see. Are you virgins?”

After a while they nodded.

“Stay that way if you can,” he said. “Then you can marry gods. Big, rich

husbands! These men are gods. But they can only marry Dirt women..."

Bidh warns them to keep away from men from lower structures of society (himself included for he is a slave), and explains their best prospects are in marrying the kind of men who captured them. His advice is benevolent enough. You might say Bidh wants the best for them, seeing his sister in these two sisters. At the same time, the girls probably cannot wrap their heads around his words. Is their best hope really marrying the kind of men who kill children and enslave them?

We learn one crucial piece of information. The City men can only marry Dirt women. So, all of them have to either buy a slave woman or capture one to get married. So, if Bela wants to ever get married, he cannot marry a free woman, or a women of his own people. Who marries those women?, you might ask, and Le Guin will answer that question shortly. What is important here to realize that while what Bela does is monstrous, he's not just psychopath who goes on killing and enslaving people. He was born into this social structure, and it's all he knows. It has never occurred to him that life could be organized any other way.

THE UNDERLYING MESSAGE- THIS IS SOMETHING THAT COULD HAPPEN TO ALL OF US!

As humans, we're often not even aware of how social constructs and organization influences us. Humans are social beings, and they tend to live in social structures. Sometimes those social structures mean having to live with monstrous choices. For a slave owner like Bela, the choices are also limited. Not justifying what he does, for it is beyond justification, just saying that all of can happen to find ourselves in a situation of choosing the lesser evil. In fact, the world we live in often gives us just that, the choice of lesser evil.

THE GUIDE BIDH CONTINUES TO CARE FOR CHILDREN, TRYING TO EASE THEIR TRANSITION

It would be easy to criticize Bidh for trying to ease transition in what is essentially a slavery, but he really has the best interest of these children at heart. What choice he has himself? Bidh can escape into wilderness, but that means leaving his sister and nephew behind, the only family he has. Remaining a slave is the best choice he sees for himself, for he is trying to use his influence as guide to change life. We see that Bidh is essentially a kind man, but one unable to change to system he lives in. That is why slavery is so devasting. Once you're in the system, it's almost impossible to escape.

Their captors now ignored them, leaving Bidh to look after them. It was

some comfort to have a man who spoke their language with them. He was

kind enough, carrying the little ones, sometimes two at a time, for he was

strong. He told Vui and Modh stories about the place where they were going.

Vui began to call him Uncle. Modh would not let him carry Mal, and did not

call him anything.

WE LEARN MORE ABOUT MODH AND HOW IT HAPPENED THAT SHE FOLLOWED THE MEN

Bela and his men wondered how it happened that Modh didn't call out anyone, and now we know. When she saw the elders killed in the chaos, she didn't run away with the other children, for she had no mother to run to. Instead, she followed the men, and that also explains how she managed to catch up with them while the others didn't. By the time the escaped older children reached their parents, it was too late for the parents to capture the murderers of their kin. Modh and her sister Mal are the main characters in this story. We see the start of their story is tragic, but we also see their strength.

Modh was eleven. When she was six, her mother had died in childbirth,

and she had always looked after the little sister.

When she saw the golden man pick up her sister and run down the hill,

she ran after them with nothing in her mind but that she must not lose the

little one. The men went so fast at first that she could not keep up, but she did

not lose their trace, and kept after them all that day. She had seen her

grandmothers and grandfathers slaughtered like pigs. She thought everybody

she knew in the world was dead. Her sister was alive and she was alive. That

was enough. That filled her heart.

When she held her little sister in her arms again, that was more than

enough.

THE MEN RETURN INTO THE CITY AND BELA REFLECTS ON WHAT HAPPENED

Bela reflects on what happened. What I found chilling is that there doesn't seem to be any regret. He sees the killing he did as something unavoidable. When you grow up in a society that is morally warp, you become morally warped yourself. However, the young Bela seems to think rationally. Even if his thoughts are avoid of what appears to us as normal human emotion, we must understand that is something that happens to most people. They let the society do the thinking for them, they don't question the morals of the society- and as hard it is to admit, that happens to us as well.

BELA TEN BELEN AND HIS COMPANIONS did not return to the City in triumph, since they had not

fought with other men; but neither did they have to creep in by back ways at

night as an unsuccessful foray. They had not lost a man, and they brought

back six slaves, all female. Only Ralo ten Bal brought nothing, and the others

joked about him losing his catch and falling asleep on watch. And Bela ten

Belen joked about his own luck in catching two fish on one hook, telling how

the marsh-fire girl had followed them of her own will to be with her sister.

BELA HONORS THE SLAVE BIDH BY BRININGING HIM CLOSER TO HIS SISTER

From the perspective of the horrible raid, Bela appears to be a monster. However, as he reflects on the events, we see there's kindness in him. Bela is not an arrogant men, he judges that he 'success' of the raid was due to slave Bidh, and so he buys Bidh and reunites him with his sister. Moreover, we learn that Bela went on the raid because he wanted his future wife to be brought up with his mother. His own mother was once a slave and brought up in his household. When you look at it like that, doesn't it seem like a more human way of doing things?

As he thought about his foray, he realized that they had been lucky

indeed, and that their success was due not to him, but to Bidh. If Bidh had

told them to do so, the Allulu would have ambushed and killed the soldiers

before they ever reached the farther village. The slave had saved them. His

loyalty seemed natural and expectable to Bela, but he honored it. He knew

Bidh and his sister Nata were fond of each other, but could rarely see each

other, since Bidh belonged to the Hans and Nata to the Belens. When the

opportunity arose, he traded two of his own house-slaves for Bidh and made

him overseer of the Belen House slave compound.

Bela had gone slave-catching because he wanted a girl to bring up in the

house with his mother and sister and his brother’s wife: a young girl, to be

trained and formed to his desire until he married her.

Bela wants the girls to grow up in his house, so in a way he wants to take care of them, and protect them. True, he's doing it for selfish reason, but those selfish reasons are not as simple as it seems. Sure, the reader might argue that the moral choice for him would simply be not to get married at all. What kind of life is that, one of solitude, with no children or wife?

IS BELA A WICKED MAN OR IS TRUTH A BIT MORE COMPLEX?

It turns out that Bela is not the monster he seems. Surely, Bela is not an independent thinker who questions the morals of slave society, but most men aren't. Most humans aren't. More often than not, as individuals we adapt to the society, not the other way around. Bela wants his future wife to grow up treated with respect. When one puts it like that, he doesn't seem the typical villain. It seems that he wants a wife that will be his equal in a way, one that won't have to be afraid of him, one that will confide in him. Ursula Le Guin also explains this not the norm, as some men prefer just to take a wife from slave quarters.

Some Crown men were content to take their Dirt wife from the dirt, from

the slave quarters of their own compound or the barracks of the city, to get

children on her, keep her in the hanan, and have nothing else to do with her.

Others were more fastidious. Bela’s mother Hehum had been brought up from

birth in a Crown hanan, trained to be a Crown’s wife. Nata, four years old

when she was caught, had lived at first in the slave barracks, but within a few

years a Root merchant, speculating on the child’s beauty, had traded five male

slaves for her and kept her in his hanan so that she would not be raped or lie

with a man till she could be sold as a wife. Nata’s beauty became famous, and

many Crown men sought to marry her. When she was fifteen, the Belens

traded the produce of their best field and the use of a whole building in

Copper Street for her. Like her mother-in-law, she was treated with honor in

the Belen household.

Finding no girl in the barracks or hanans he was willing to look at as a

wife, Bela had resolved to go catch a wild one. He had succeeded doubly.

BELA DECIDES TO BRING OUT BOTH SISTERS IN HIS HOME

At first Bela thinks of sending the older sister to the barracks for she doesn't seem a beauty at that point, but his courage in following him impressed him, and so decides to keep them both to be brought up in his home by his mother, grandmother and sister-in-law. It is also clearly indicated that Bela has interest in neither of sisters while they are children and indents to wait until they're fully grown. So, there's some relief in knowing that Bela is not a complete monster. What is the life going to be like for the sisters in his household? Actually, as we are to learn these two are going to be showered with love from the women in the house and brought up as they were their own children.

It was strange to the wild girls to hear Nata Belenda speak words of their

language, for to them she seemed a creature of another order, as did Hehum

Belenda, the mother of Bela and Alo, and Tudju Belen, the sister. All three

women were tall and clean and soft-skinned, with soft hands and long lustrous

hair. They wore garments of cobweb colored like spring flowers, like sunset

clouds. They were goddesses. But Nata Belenda smiled and was gentle and

tried to talk to the children in their own tongue, though she remembered little

of it. The grandmother Hehum Belenda was grave and stern-looking, but quite

soon she took Mal onto her lap to play with Nata’s baby boy. Tudju, the

daughter of the house, was the one who most amazed them. She was not

much older than Modh, but a head taller, and Modh thought she was wearing

moonlight. Her robes were cloth of silver, which only Crown women could

wear. A heavy silver belt slanted from her waist to her hip, with a marvelously

worked silver sheath hanging from it. The sheath was empty, but she

pretended to draw a sword from it, and flourished the sword of air, and lunged

with it, and laughed to see little Mal still looking for the sword. But she

showed the girls that they must not touch her; she was sacred, that day. They

understood that.

THE GIRLS LEARN ABOUT THE CROWN WOMAN AND THEIR LIFE

After three months they attended their first ceremony at the Great

Temple: Tudju’s coming of age. They all went in procession to the Great

Temple. To Modh it was wonderful to be out in the open air again, for she was

weary of walls and ceilings. Being Dirt women, they sat behind the yellow

curtain, but they could see Tudju chose her sword from the row of swords

hanging behind the altar. She would wear it the rest of her life whenever she

went out of the house. Only women born to the Crown wore swords. No one

else in the City was allowed to carry any weapon, except Crown men when

they served as soldiers. Modh and Mal knew that, now. They knew many

things, and also knew there was much more to learn—everything one had to

know to be a woman of the City.

It was easier for Mal. She was young enough that to her the City rules

and ways soon became the way of the world. Modh had to unlearn the rules

and ways of the Tullu people. But as with the language, some things were

more familiar than they first seemed. Modh knew that when a Tullu man was

elected chief of the village, even if he already had a wife he had to marry a

slave woman. Here, the Crown men were all chiefs. And they all had to marry

Dirt women—slaves. It was the same rule, only, like everything in the City,

made greater and more complicated.

SLAVERY IS NOT AS ALIEN CONCEPT TO THE GIRLS AS I ORIGINALLY THOUGHT

Mal and Modh tribe also kept slaves. In a way, their life here is similar, only more complicated.

In the village, there had been two kinds of person, Tullu and slaves. Here

there were three kinds; and you could not change your kind, and you could

not marry your kind. There were the Crowns, who owned land and slaves, and

were all chiefs, priests, gods on earth. And the Dirt people, who were slaves.

Even though a Dirt woman who married a Crown might be treated almost like

a Crown herself—like the Nata and Hehum—still, they were Dirt.

THE SOCIETY IS ORGANIZED INTO CASTES, WITH CROWN MEN MARRYING SLAVES AND THE CROWN WOMEN MARRYING ROOTS (AN IN-BETWEEN CLASS)

No wonder that Tudju doesn't want to marry! I felt bad for her, as she might be forced to marry someone she doesn't want to, just to increase the family fortune. At the same time, Crown women are allowed to carry swords and actually the only ones allowed to carry weapons. Is it to protect themselves?

And there

were the other people, the Roots.

Modh knew little about the Roots. There was nobody like them in her

village. She asked Nata about them and observed what she could from the

seclusion of the hanan. Root people were rich. They oversaw planting and

harvest, the storehouses and marketplaces. Root women were in charge of

housebuilding, and all the marvelous clothes the Crowns wore were made by

Root women.

Crown men had to marry Dirt women, but Crown women, if they

married, had to marry Root men. When she got her sword, Tudju also

acquired several suitors—Root men who came with packages of sweets and

stood outside the hanan curtain and said polite things, and then went and

talked to Alo and Bela, who were the lords of Belen since their father had

died in a foray years ago.

AN INTERESTING DETAIL- A ROOT WOMEN WANTS TO BUY BIDH AND HE'S GIVEN A FREE CHOICE

So, basically the root people are a society level between slaves and slave owners. They are a merchant class if you will, farmers that farm the lands and produce the food. One of these people want to buy Bidh and marry him. So, basically the men from the top of the hierarchy aka the Crown men marry slaves and those slave wives then have a high status in many cases. Meanwhile, Crown women have to marry the lower class men, and the lower class woman buy slaves to marry? A complicated system, but not that complicated. As Modh notices it's not that different from the slave. What makes it different is that for every level of society, the rules for men and women are different. Slave women can rise from being a slave to being adored as a goddess (as in case of Nata), whereas the same isn't possible for men. Moreover, woman from the highest rank are expected to marry merchants and increase their family fortune by doing so. They are basically sentenced to marrying beneath them.

Why this complex social system? It could be prevent inbreeding, but if you look at our human history, it is not without precedent. If you look at our present human society, where slavery is still sadly widespread, you'll see that cases like this happen.

Root women had to marry Dirt men. There was a Root woman who

wanted to buy Bidh and marry him. Alo and Bela told him they would sell

him or keep him, as he chose. He had not decided yet.

So, at least Bidh gets to choose whether to marry or not, indicating he has some level of liberty. Still, what kind of liberty is that? What kind of liberty does anyone has in a slave owning society? Isn't every liberty an illusion? The sword that Bela's sister's wears- what good is it really? She has a choice between being a priestess (what she wants but may not get) and being a wife to some prosperous merchant? Bela's sister cannot marry for love. Can he? Bela wants his future wife to be brought in his house, and that is in some way kindness for there she will be safe and cared for...but on the other hand, how can his future wife ever forget where she came from? Isn't there a seed of doubt always and in everyone in a society where human beings can be reduced to property and bought and sold?

NATA EXPLAINS THE SYSTEM CALMLY, AND REALLY NEITHER NATA NOR MODH CAN SEE THE SYSTEM AS DEEPLY INJUST BECAUSE THEY HAVE NEVER LIVED IN A JUST SYSTEM

Root people owned slaves and crops, but they owned no land, no houses.

All real property belonged to Crowns. “So,” said Modh, “Crowns let the Root

people live in the City, let them have this house or that, in exchange for the

work they do and what their slaves grow in the fields—is that right?”

“As a reward for working,” Nata corrected her, always gentle, never

scolding. “The Sky Father made the City for his sons, the Crowns. And they

reward good workers by letting them live in it. As our owners, Crowns and

Roots, reward us for work and obedience by letting us live, and eat, and have

shelter.”

Modh did not say, “But—

It was perfectly clear to her that it was a system of exchange, and that it

was not fair exchange. She came from just far enough outside it to be able to

look at it. And, being excluded from reciprocity, any slave can see the system

with an undeluded eye. But Modh did not know of any other system, any

possibility of another system, which would have allowed her to say “But.”

Neither did Nata know of that alternative, that possible even when

unattainable space in which there is room for justice, in which the word “But”

can be spoken and have meaning.

Sometimes we're not even aware of the freedom and the opportunities we have. To understand the monstrous injustice of slavery, one needs to live outside of the system.

NATA SHOWERS MOTHERLY LOVE ONTO THE GIRLS

Nata had been raised with kindness, so she cared for the girls the same way. However, where is true kindness? Nata loves the girls because they are 'her people' but at the same time, both she and the girls silently accept being in this new world. What choice do they have? They have never seen a fair system or lived in a fair society, so they have no 'but' to utter. They cannot complain of injustice, for all they have ever known is injustice. They take the kindness where they can, and accept being wives to men who while might treat them with some love, are their captors. I wonder if we could really look our human society from a point of view of an alien visiting our planet, wouldn't we be horrified as well? Slavery exists on our planet as well, as do numerous injustices.

Nata had undertaken to teach the wild girls how to live in the City, and

she did so with honest care. She taught them the rules. She taught them what

was believed. The rules did not include justice, so she did not teach them

justice. If she did not herself believe what was believed, yet she taught them

how to live with those who did. Modh was self-willed and bold when she

came, and Nata could easily have let her think she had rights, encouraged her

to rebel, and then watched her be whipped or mutilated or sent to the fields to

be worked to death. Some slave women would have done so. Nata, kindly

treated most of her life, treated others kindly. Warm-hearted, she took the girls

to her heart. Her own baby boy was a Crown, she was proud of her godling,

but she loved the wild girls too. She liked to hear Bidh and Modh talk in the

language of the nomads, as they did sometimes. Mal had forgotten it by then.

THE GIRLS LIVE PRIVILEGED LIFE OR SO IT SEEMS

Compared with the life other women and girls are leading, Mal and Modh's life seems comfortable enough. Not only are Mal and Modh spoiled, they are not required to do any work, and being allowed to play with Bela's sister Tudju saves them from boredom.

Mal soon grew out of her plumpness and became as thin as Modh. After

a couple of years in the City both girls were very different from the tough

little wildcats Bela ten Belen’s foray had caught. They were slender, delicatelooking. They ate well and lived soft. These days, they might not have been

able to keep up the cruel pace of their captors’ flight to the City. They got

little exercise but dancing, and had no work to do. Conservative Crown

families like the Belens did not let their slave wives do work that was beneath

them, and all work was beneath a Crown.

Modh would have gone mad with boredom if the grandmother had not

let her run and play in the courtyard of the compound, and if Tudju had not

taught her to sword-dance and to fence. Tudju loved her sword and the art of

using it, which she studied daily with an older priestess. Equipping Modh

with a blunted bronze practice sword, she passed along all she learned, so as

to have a partner to practice with. Tudju’s sword was extremely sharp, but she

already used it skillfully and never once hurt Modh.

Tudju had not yet accepted any of the suitors who came and murmured

at the yellow curtain of the hanan. She imitated the Root men mercilessly

after they left, so that the hanan rocked with laughter. She claimed she could

smell each one coming—the one that smelled like boiled chard, the one that

smelled like cat-dung, the one that smelled like old men’s feet.

Fencing is an activity both girls enjoy. However, are they able to use those weapons to really save themselves? How can they escape a system that is rotten at its core? Especially when they have never known a different world? Modh and Tudju play together like sisters, but at the same time they are separated by the castes they belong to. They might not have any work to do, they might have a roof over their head, fine clothes and food, but they are not truly free. Certainly, there's comfort in being raised with women who care for them, especially since Modh and Mal didn't have a mother while nomads, but they are still slaves. In a way, so is Tudju. In a way, so is everyone.

TUDJU DOESN'T WANT TO GET MARRIED BUT SHE MAY HAVE TO

Crown people are called Gods, but they are nothing of the sort. They are just a more wealthy class, and as such bound by their wealth. Wealth can be captor, too. The Beren family have to manage their finances if they want to continue to live on their level. That's what fascinating about slavery, in the end it makes everyone poor. Yes, some people have more than others, but there is no real progress, no real safety as everyone lives in fear and uncertainty. We can see that Belen brothers expect their sister Tudju to marry for money, and she might have to listen to them. They are not Gods, they live paycheck to paycheck like the majority of people in an economy that doesn't work well.

She told

Modh, in secret, that she did not intend to marry, but to be a priestess and a

judge-councillor. But she did not tell her brothers that. Bela and Alo were

expecting to make a good profit in food-supply or clothing from Tudju’s

marriage; they lived expensively, as Crowns should. The Belen larders and

clothes-chests had been supplied too long by bartering rentals for goods. Nata

alone had cost twenty years’ rent on their best property.

MODH MAKES FRIENDS BUT STILL SHE LOVES HER SISTER BEST OF ALL

Modh's reason for living is still her sister Mel, who is really a daughter of sorts for her. It's the love for her sister that keeps Modh at check. She was old enough to remember what men did, but for her sister's sake, she tries to forget the past and focus on the present.

Modh made friends among the Belenda slaves and was very fond of

Tudju, Nata, and old Hehum, but she loved no one as she loved Mal. Mal was

all she had left of her old life, and she loved in her all that she had lost for her.

Perhaps Mal had always been the only thing she had: her sister, her child, her

charge, her soul.

MODH THINKS OF HER PEOPLE AND REMEMBERS THE TRAGEDY

Modh understand the way of the new world, understands that she will never see her father again. As in that fateful night, she choses to focus on her sister, to live for her and to forget that she lives in a house of a man who killed her grandparents.

She knew now that most of her people had not been killed, that her father

and the rest of them were no doubt following their annual round across the

plains and hills and waterlands; but she never seriously thought of trying to

escape and find them. Mal had been taken, she had followed Mal. There was

no going back. And as Bidh had said to them, it was a big, rich life here.

She did not think of the grandmothers and grandfathers lying

slaughtered, or Dua’s Daughter who had been beheaded. She had seen all that

yet not seen it; it was her sister she had seen. Her father and the others would

have buried all those people and sung the songs for them. They were here no

longer. They were going on the bright roads and the dark roads of the sky,

dancing in the bright hut-circles up there.

MODH DOESN'T HATE BELA TEN BELEN

What is fascinating is that Modh doesn't hate Bela. In her world, men do the killing, and one neither loves nor hates them for it. Modh has a vary view of men, choosing to focus her attention on Mal, her sister, her daughter, her soul.

She did not hate Bela ten Belen for leading the raid, killing Dua’s

Daughter, stealing her and Mal and the others. Men did that, nomads as well

as City men. They raided, killed people, took food, took slaves. That was the

way men were. It would be as stupid to hate them for it as to love them for it.

Women and men are not equal in this class society. Throughout the classes, they are separated by unspoken rules. Underneath it all, all of is there is fear and trauma. There is no true love, or hardly any.

BUT SOMETHING STILL HAUNTS HER...A REMAINDER OF THE TRAUMA

Modh cannot shake off one thing, nor can her sister. When one child died during the raid, or was killed by neglect, it wasn't buried. According to the tradition of their people, it means that the ghost will haunt them. This part reminded me of Beloved of Toni Morrison. This part of the story can be read in two ways. The reader can imagine that the sisters are hallucinating the child spirit as a result of the trauma that happened to them, or the reader can believe they are really seeing the spirit. Either way, it is easy to sympathize with the sister's ordeal and fear.

But there was one thing that should not have been, that should not be and

yet continued endlessly to be, the small thing, the nothing that when she

remembered it made the rest, all the bigness and richness of life, shrink up

into the shriveled meat of a bad walnut, the yellow smear of a crushed fly.

It was at night that she knew it, she and Mal, in their soft bed with

cobweb sheets, in the safe darkness of the warm, high-walled house: Mal’s

indrawn breath, the cold chill down her own arms, do you hear it?

They clung together, listening, hearing.

Then in the morning Mal would be heavy-eyed and listless, and if Modh

tried to make her talk or play she would begin to cry, and Modh would sit

down at last and hold her and cry with her, endless, useless, dry, silent

weeping. There was nothing they could do. The baby followed them because

she did not know whom else to follow.

Neither of them spoke of this to anyone in the household. It had nothing

to do with these women. It was theirs. Their ghost.

Sometimes Modh would sit up in the dark and whisper aloud, “Hush,

Groda! Hush, be still!” And there might be silence for a while. But the thin

wailing would begin again.

MAL AND MOTH- TWO CHILD SURVIVORS BUT WHAT WILL BECOME OF THEM?

I retold the first part of the story, but it's only the beginning really. Mal and Moth won't remain children forever. Soon, their time to marry will come. Their friends were sold, they have nobody they known in this world. Will they marry? Will they become God wives? Will one of them marry the men who killed their grandparents? Will he be kind to them? Will any amount of kindness made them forget Bella killed a child during the rain and let another die? Will the ghost of a child died follow them? To find the answers to those questions, you'll have to read the story.

CONCLUSION- URSULA LE GUIN CREATES A CHILLING AND CREDIBLE TALE OF SLAVERY

I liked how Urusla K Le Guin avoided stereotypes in crafting her characters. Many of the characters are kind to a degree, but still cursed simply by belonging to this world. Cursed by the curse of slavery, that poisons the society from within.

Only one men is a real villain or a monster if you will, the others are morally grey characters. You hate what they do, but you cannot call them monsters. They are a part of the system, and simply do not know better. As we learn more about this world, we understand that slavery is just a part of it.

Le Guin shows us both human weaknesses and strengths, shows us how the instinct for survivor is strong, and how we as humans are highly adaptable. Is this adaption for the good or for the worse? Nata adapts successfully, and is a loving mother to her son, a loving sister to her brother- but I wonder how she truly feels about her husband. What we learn of Nata is that she is celebrated for her beauty. Does her husband truly love her or is he proud of her pretty face?

Is Nata truly well adjusted? Has she truly forgotten the night she was taken, the trauma of it? Perhaps she has, but still the fact remains that she is not truly free. Nobody is. Nobody can be. Humans are social animals. When the society they live is built all wrong, there is little hope for happiness.

The nomad world isn't a paradise either. It's filled with hard work, and slavery exists there as well. Tribes fight one another, and the city people when they venture into their territory. What is even a moral choice for a woman in this society? Is it wrong for her to forgive men for what they do? Is it when there's nowhere to turn?

Gender is also a part of this story. Men and women are strong and weak in different ways. This society with its caste system alienates men from women and poisons their relationships. For girls like Moth and Mal, men are something that is tolerated, not loved. For men like Bela, women are something that is needed, but not loved beyond a certain degree.

You will not find deep romantic love in this story. How can in exist where there is no freedom? Where neither men or women are able to choose their partner freely? The closest you'll get to love is sisterly love, the relationship existing between the two nomad's girls.

Speaking of them, I was really impressed with how Ursula managed to convey their inner states to us. For such a short work of prose, The Wild Girls manages to capture the soul of its protagonists in a convincing and touching way.

To conclude, The Wild Girls is a sad but cathartic story that dives into the tragedy of being human in an unhuman world. Highly recommended!

WHAT IS THE LAST THING BY LE GUIN I'VE READ? ACTUALLY, IT'S ANOTHER SHORT STORY THAT I WOULD LIKE TO RECOMMEND!

I posted this review in August this year. The short story in question is titled The Masters. It's one of Ursula's early works. If I'm not mistaken, it's her first or second published work. Some sources list is as first publish work, some as the second one. Published in 1963, this short story is set in a dystopian future. It opens with a young protagonist undergoing an initiation of some kind. Soon, we as readers learn more about this initiation as well as the dystopian society he lives in. It's a preindustrial sort of world where the Sun is only occasionally seen. It's possible that what Ursula describes is a future on planet Earth. It's a bleak future, where people are prosecuted for expressing interest in Science and Math.

IN CASE YOU WANT MORE LE GUIN READING RECOMMENDATION CHECK OUT THIS LIST!

WELL, THE LIST IS LONG! I REVIEWED MANY OF HER WORKS ON MY BLOG, SO HERE ARE THE LINKS TO MY READING RECOMMENDATIONS

FIRST OF ALL- THE EARTHSEA CYCLE

PERFECT FOR LOVERS OF FANTASY!

IF EARTHSEA CYCLE ISN'T YOUR THING, WHY NOT CHECK OUT HER OTHER WORK?

URSULA K. LE GUIN'S BOOK REVIEWS ON MY BLOG

1. THE WORD FOR WORLD IS A FOREST (A NOVELLA)

This novella is an absolute masterpiece! Poetically written, profoundly serious and wonderfully imaginative, The Word for World is a Forest is an exceptional book. The story Le Guin created is a incredibly tragic and sad one, but it rings absolutely true in its sadness and tragedy.

2. THE TELLING (A NOVEL)

The Telling in the novel's title is actually a philosophy (or a religion if you will) based on Taoism. I loved Le Guin's take on Taoist inspired religion/philosophy know as 'The Telling' in the novel. It seems to me that Le Guin is well acquainted with Taoism and Buddhism, so well acquainted she is able to summon some of the complexity of Asian theologies, myths and philosophy in this novel, something I imagine is not easy to do.

3. THE LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS (A NOVEL)

The Left Hand of Darkness is a brilliant novel set on a planet whose culture is quite different from our own. It questions gender identity in the most brilliant of ways. This is a novel way ahead of its time. One of the best novels I have ever read for sure!

4. THE DISPOSSESSED (A NOVEL)

The Dispossessed is an Utopian (at times Dystopian) philosophical science fiction novel with a developed plot, charismatic protagonist and detailed world building. Focusing on social and philosophical themes, The Dispossessed is written in a non-chronological way.

Thank you for reading!

ReplyDeleteThe blouse you're wearing under the blazer is very pretty. And I love the photos of you sitting in the chair. A great motif and an incredibly beautiful outfit.

Wish you a nice evening

Thank you!

DeleteSuper photos. I love the hat. The photo on the phone is amazing :-D

ReplyDeleteThanks dear.

DeleteYou are so cool, thanks for your sharing

ReplyDeleteThank you for commenting!

DeleteTengo pendiente a ese libro. Me encanta esa autora. Te mando un beso.

ReplyDeletegracias!

Deleteun beso!

Dear Ivana! Thank you for telling about Ursuls K. Le Guin and her book. I am sorry but I didn't read h "The Wild Girls". But I'd like to read it.

ReplyDeleteI hope you will like it!

DeleteDear Ivana! Thank you for telling about Ursuls K. Le Guin and her book. I am sorry but I didn't read h "The Wild Girls". But I'd like to read it.

ReplyDeleteYou can find pdf versions of this story online if you'd like to read it. It's a very serious and sad story, but I think it's worth the effort.

DeleteDear Ivana, without any pretentiousness, but you write the best reviews in the world!!! If there was a Nobel Prize for that, you'd be the first to win it :) I'm not kidding, it's true. Your photos are phenomenal as always! 👍👏👏👏👏👏

ReplyDeleteThank you very much!

DeleteA very interesting book with a great message and really wonderful review. Love also your outfits!

ReplyDeleteThank you very much!

DeleteSo great to explore her theme of slavery in Wild Girls. You always find such amazing authors. It is good to know more about her. So many wonderful outfits from your wardrobe too as you transition into fall! Thanks for this mega-post on Wild Girls, your fashion and your art too. All the best to being inspired! Thanks again, for your comments and much much more!

ReplyDeleteUrsula is an amazing author for sure. Thank you for your support!

DeleteThis is great to read your insightful review on the story and about the author. Such a haunting storyline..how it starts out so small and then becomes a massive storyline. Love the photos, too. So cool to see you in a black suit! You wear it well! Love seeing these skirts too. You are so inspiring. Thanks for reading and thank you for your comments. All the best to a fun and productive October! 💛🍁🍂💕🖤🎃

ReplyDelete:):) I wish you a fantastic October as well

DeleteHello Ivana! Ursula K. Le Guin is one of my favorite fantasy, s/f authors. But I don't think I've read this story. She was a very prolific and widely read writer and many of her works were translated into my language. Thank you for the recommendation - I will look for this book.

ReplyDeleteYou look great as always, your paintings and photos are also amazing.

Best regards and have a good new week. Hugs.

Thank you so much! I hope you enjoy it.

DeleteWhat a well-written and in-depth synopsis, Ivana. You ought to write reviews for a living!

ReplyDeleteFabulous photos, I love the picture of you in your floral maxi overlooking the cliffs! xxx

Thank you Vix! I enjoy writing book reviews. It reminds of my Uni years, writing about the books we studied.

DeleteThat is a really wonderful story. Thanks for sharing. You paintings are all so beautiful.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate it.

DeleteI didn't know this author but your review of the book has made me curious. I'll see if I can get it in my city. The stories about slavery are definitely deep and not easy to assimilate. I loved the photos that accompanied your review, especially the ones where you appear with your paintings.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much. I try to make my reviews visually interesting.

DeleteYour review of Ursula K. Le Guin's The Wild Girls is profound and insightful. It's clear how deeply this story resonated with you, and your analysis highlights the complexities and emotional depth of the narrative. Le Guin's ability to tackle such difficult themes with grace and power is truly remarkable.

ReplyDeleteWishing you a great day. Read my new post: https://www.melodyjacob.com/2024/10/ultra-rich-anti-aging-cream-for-improved-skin-hydration-and-radiance.html

Thank you Melody!

Delete