MEMOIRS OF HADRIAN BY MARGUIRETE YOURCENAR (PART ONE)- BOOK REVIEW

Hello, dear readers! I'm back with another book review and recommendation. Memories of Hadrian by Belgian French author Marguerite Yourcenar is an extraordinary novel about Roman emperor Hadrian. Published in 1951, it won its author critical acclaim and was an immediate success. Originally written and published in French, under the title Mémoires d'Hadrien, it was translated to English in 1954 by Grace Frick, who was not only Marguirete's lifelong translator but also her lifelong partner.

Belgian born Marguerite Yourcenar became an USA citizen in 1954, the same year an English version of her novel was published. Marguerite was quite an established writer, the winner of the Prix Femina and the Erasmus Prize, and the first woman elected to the French Academy in 1980. In 1965, she was even nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature. Surely, this novel had something to do with her success. It is said that Marguerite envisioned this novel when she was about twenty years old, but she cast away her original writings and manuscripts. Over the span of about ten years, Marguerite kept returning to her work, until she finally finished and published this masterpiece.

Calling it a masterpiece seems justified. Memories of Hadrian might just be one the finest historical novel I have read. Not only it is meticulously researched and well plotted, it's amazing philosophical and lyrical. The beautifully lyrical writing feels absolutely authentic, and it flows so easily, it's almost hypnotic. Not only do you feel like you're reading actual autobiography written by Hadrian itself, you feel like you have insight into the depths of his soul. The writing style is so intimate and the psychological analysis of Hadrian so well done, you feel as if you're his confessor.

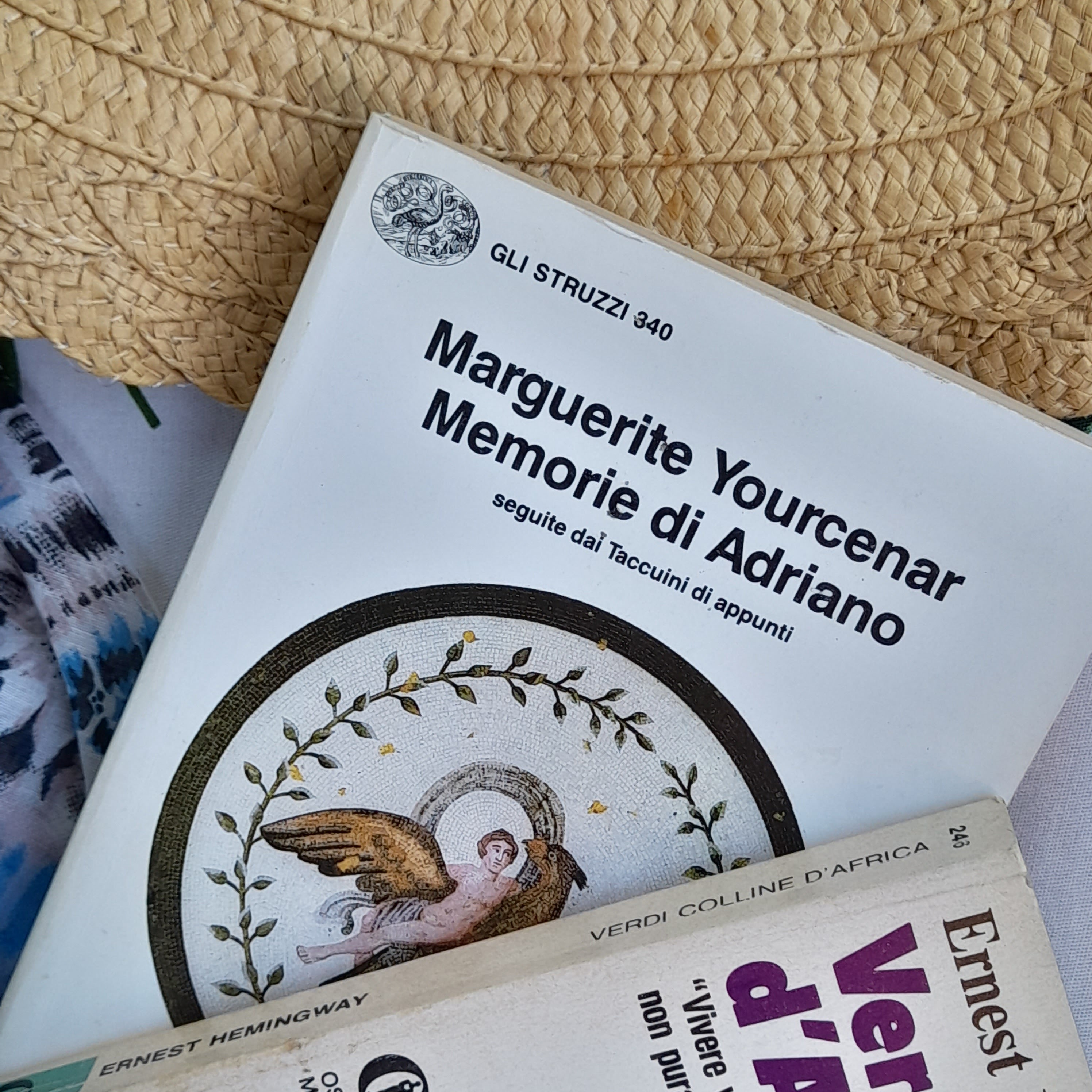

My book review is going to be longer than usual and therefore, I plan to divide it into two parts! I'm reading the book in Italian. I bought this Italian edition in a secondhand bookshop in Split where I get all of my vintage editions. The book is so pretty. It's also in wonderful state. Not that I mind shabby books, I actually enjoy that too. I can't wait for this book to become shabby as well, but for the moment I'm enjoying its being in pristine condition.

I'm really enjoying reading this novel. There's also an audiobook in Italian that I'm listening simultaneously. Here is the Youtube link. I also checked out the English translation. Moreover, the quotations I'm going to use are going to be in English, because that's the language of this review. I do recommend reading this book in original or one of the Latin languages. The reason for it that the author went to great lengths using words of Latin or Greek origin so that the novel would feel more Latin.

I will use quotations from Internet Archive.*

source https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.125737/2015.125737.Memoirs-Of-Hadrian_djvu.txt.

- Oh, loving Soul, my own so tenderly,

- My life’s companion and my body’s guest,

- To what new realms, poor flutterer, wilt thou fly?

- Cheerless, disrobed, and cold in thy lone quest,

- Hushed thy sweet fancies, mute thy wonted jest.

ANIMULA VAGULA, BLANDULA,

HOSPES COMESQUE CORPORIS,

QUAE NUNC ABIBIS IN LOCA

PALLIDULA, RIGIDA, NUDULA,

NEC, UT SOLES, DABIS IOCOS. . .

P. AELIUS HADRIANUS, IMP ANIMULA VAGULA BLANDULA

My dear Mark,

Today I went to see my physician Hermogenes, who has just returned to the Villa from a rather long journey in Asia.

No food could be taken before the examination, so we had made the appointment for the early morning hours. I took off

my cloak and tunic and lay down on a couch. I spare you details which would be as disagreeable to you as to me, the

description of the body of a man who is growing old, and is about to die of a dropsical heart. Let us say only that I coughed,

inhaled, and held my breath according to Hermogenes’ directions. He was alarmed, in spite of himself, by the rapid progress

of the disease, and was inclined to throw the blame on young Iollas, who has attended me during his absence. It is difficult

to remain an emperor in the presence of a physician, and difficult even to keep one’s essential quality as man. The

professional eye saw in me only a mass of humours, a sorry mixture of blood and lymph. This morning it occurred to me

for the first time that my body, my faithful companion and friend, truer and better known to me than my own soul, may

be after all only a sly beast who will end by devouring his master. But enough I like my body; it has served me well,

and in every way, and I do not begrudge it the care it now needs.

I have no faith, however, as Hermogenes still claims to have in the miraculous virtues of herbs, or the specific mixture of

mineral salts which he went to the Orient to get. Subtle though he is, he has nevertheless offered me vague formulas of re-

assurance too trite to deceive anyone; he knows how I hate this kind of pretence, but a man does not practise medicine for more

than thirty years without some falsehood. I forgive this good servitor his endeavour to hide my death from me. Hermogenes

is learned; he is even wise, and his integrity is well above that of the ordinary court physician. It will fall to my lot as a sick

man to have the best of care. But no one can go beyond prescribed limits : my swollen limbs no longer sustain me through

the long Roman ceremonies; I fight for breath; and I am now sixty. Do not mistake me; I am not yet weak enough to yield to

fearful imaginings, which are almost as absurd as illusions of

hope, and are certainly harder to bear. If I must deceive

myself, I should prefer to stay on the side of confidence, for

I shall lose no more there and shall suffer less.This approaching end is not necessarily immediate; I still retire each night

with hope to see the morning. Within those absolute limits of

which I was just now speaking I can defend my position step

by step, and even regain a few inches of lost ground. I have

nevertheless, reached the age where life, for every man, is

accepted defeat. To say that my days are numbered signifies

nothing; they always were, and are so for us all. But uncertainty as to the place, the time, and the manner, which keeps

us from distinguishing the goal toward which we continually

advance, diminishes for me with the progress of my fatal malady.

A man may die at any hour, but a sick man knows that he will

no longer be alive in ten years’ time. My margin of doubt is

a matter of months, not years. Shall I be carried off by the tenth of these crises, or the hundredth ? That is the only question.

Like a traveller sailing the Archipelago who sees

the luminous mists lift toward evening, and little by little

makes out the shore, I begin to discern the profile of my

death. Already certain portions of my life are like dismantled rooms

of a palace too vast for an impoverished owner to occupy in

its entirety. I can hunt no longer: if there were no one but

me to disturb them in their ruminations and their play the

deer in the Etrurian mountains would be at peace. With the Diana of the forests I have always maintained the swift-chang-

ing and passionate relations which are those of a man with the

object of his love: the boar hunt gave me my first chance, as

a boy, for command and for encounter with danger; I fairly

threw myself into the sport, a r.d my excesses in it brought

reprimands from Trajan. The kill in a Spanish forest was my

earliest acquaintance with death and with courage, with pity

for living creatures and the tragic pleasure of seeing them

suffer. Grown to manhood, I found in hunting release from

many a secret struggle with adversaries too subtle or too stupid

in turn, too weak or too strong for me; this evenly-matched

battle between human intelligence and the wisdom of wild

beasts seemed strangely clean compared to the snares set by

men for men. My hunts in Tuscany have helped me as emperor

to judge the courage or the resources of high officials; I have

chosen or eliminated more than one statesman in this way. In

later years, in Bithynia and Cappadocia, I made the great

drives for game a pretext for festival, a kind of autumnal

triumph in the woods of Asia. But the companion of my last

hunts died young, and my taste for these violent pleasures has

greatly abated since his departure. Even here in Tibur, however,

the sudden bark of a stag in the brush is enough to set tremble

within me an impulse deeper than all the rest, by virtue, jf

which I feel myself leopard as well as emperor. Who knows ?

Possibly I have been so sparing of human blood only because

I have shed so much of the blood of wild beasts, even if some-

times, privately, I have preferred beasts to mankind. However

that may be, they are more in my thoughts, and it is hard not

to let myself go into interminable tales of the chase which

would try the patience of my supper guests. Surely the recol-

lection of the day of my adoption has its charm, but the memory

of lions killed in Mauretania is not bad either.

To give up riding is a greater sacrifice still: a wild beast isfirst of all an adversary, but my horse was a friend. If the choiceof my condition had been left to me I would have decided forthat of centaur. Between Borysthenes and me relations wereof almost mathematical precision; he obeyed me as if I werehis own brain, not his master. Have I ever obtained as muchfrom a man ? Such total authority comprises, as does any otherpower, its risk of error for the possessor, but the pleasure ofattempting the impossible in jumping an obstacle was toostrong for me to regret a dislocated shoulder or a broken rib.My horse knew me not by the thousand approximate notionsof title, function, and name which complicate human friend-ship, but solely by my just weight as a man. He shared myevery impetus; he knew perfectly, and better perhaps than I,the point where my strength faltered under my will.

When Celer leaps down from his horse I too regain contact with the

ground. It is the same with swimming: I have given it up, but

I still share the swimmer’s delight in water’s caress. Running,

even for the shortest distance, would today be as impossible

for me as for a heavy statue, a Caesar of stone; but I recall my

childhood races on the dry hills of Spain, and the game played

with myself of pressing on to the last gasp, never doubting that

the perfect heart and healthy lungs would re-establish their

equilibrium; and with any athlete training for the stadium I

have a common understanding which the intelligence alone

would not have given me. Thus from each art practised in its

time I derive a knowledge which compensates me in part for

pleasures lost. I have supposed, and in my better moments

think so still, that it would be possible in this manner to

participate in the existence of everyone; such sympathy would

be one of the least revocable kinds of immortality. There have

been moments when that comprehension tried to go beyond

human experience, passing from the swimmer to the wave.

But in such a realm, since there is nothing exact to guide me,

I verge upon the world of dream and metamorphosis. Overeating is a Roman vice, but moderation has always been

my delight. Hermogenes has had to change nothing in my diet,

except perhaps the impatience which made me devour the

first thing served, no matter where or when, in order to satisfy

the needs of hunger simply and at once. It is clear that a man

of wealth, who has never known anything but voluntary priva-

tion, or has experienced it only provisionally as one of the

more or less exciting incidents of war or travel, would have but

ill grace to boast of undereating. Stuffing themselves on certain

feast days has always been the ambition, joy, and natural pride

of the poor. At army festivities I liked the aroma of roasted

meats and the noisy scraping of kettles, and it pleased me to

see that the army banquets (or what passes for a banquet in

camp) were just what they always should be, a gay and hearty

contrast to the deprivations of working days.

Wine initiates us into the volcanic mysteries of the soil and

its hidden mineral riches; a cup of Samos drunk at noon in the

heat of the sun or, on the contrary, absorbed of a winter

evening when fatigue makes the warm current felt at once

in the hollow of the diaphragm and the sure and burning

dispersion spreads along our arteries, such a drink provides a

sensation which is almost sacred, and is sometimes too strong

for the human head. No feeling so pure comes from the vintage-

numbered cellars of Rome; the pedantry of great connoisseurs

of wine wearies me. Water drunk more reverently still, from

the hands or from the spring itself, diffuses within us the most

secret salt of earth and the rain of heaven. But even water is a

delight which, sick man that I am, I may now consume only

with strict restraint. No matter: in death’s agony itself, and

mingled with the bitterness of the last potions, I shall try still

to taste on my lips its fresh simplicity. In the schools of philosophy, where it is well to try once

for all each mode of life, I have experimented briefly with

abstention from meat; later, in Asia, I have seen the Indian

Gymnosophists avert their eyes from smoking lamb quarters

and gazelle meat served in the tent of Osroes. But this practice,

in which your youthful love of austerity finds charm, calls for

attentions more complicated than those of culinary refinement

itself; and it separates us too much from the common run of

men in a function which is nearly always public, and in which

either friendship or formality presides. I should prefer to live

all my life upon woodcock and fattened goose rather than be

accused by my guests, at each meal, of a display of asceticism.

Already I have had some trouble to conceal from my friends,

by the help of dried fruits or the contents of a glass sipped

slowly, that the display pieces of my chefs were made more

for them than for me, and that my interest in these courses

ended before theirs. A prince lacks the latitude afforded to

the philosopher in this respect: he cannot allow himself to be

different on too many points at a time; and the gods know that

my points of difference were already too numerous, though I

flattered myself that many were invisible. As to the religious

scruples of the Gymnosophist and his disgust at the sight of

bleeding flesh, I should be more affected thereby if I had not

sometimes asked myself in what essentials the suffering of

grass, when it is cut, differs from the suffering of slaughtered

sheep, and if our horror in presence of murdered beasts does

not arise from the fact that our sensations belong to the same

physical order as theirs. But at certain times of life, for example

in periods of ritual fasting or in the course of religious initia-

tions, I have learned the advantage for the mind (and also the

dangers) of different forms of abstinence, or even of voluntary

starvation, those states approaching giddiness where the body,

partly lightened of ballast, enters into a world for which it is

not made, and which affords it a foretaste of the cold and

emptiness of death.The cynics and the moralists agree in placing the pleasures

of love among the enjoyments termed gross, that is, between

the desire for drinking and the need for eating, though at the

same time they call love less indispensable, since it is some-

thing which, they assert, one can go without. I expect almost

anything from the moralist, but am astonished that the cynic

should go thus astray. Probably both fear their own daemons,

whether resisting or surrendering to them, and they oblige

themselves to scorn their pleasure in order to reduce its almost

terrifying power, which overwhelms them, and its strange

mystery, wherein they feel lost. I shall never believe in the

classification of love among the purely physical joys (supposing

that any such things exist) until I see a gourmet sobbing with

delight over his favourite dish like a lover gasping on a young

shoulder. Of all our games, love’s play is the only one which

threatens to unsettle the soul, and is also the only one in

which the player has to abandon himself to the body’s ecstasy.

To put reason aside is not indispensable for a drinker, but the

lover who leaves reason in control does not follow his god to

the end. In every act save that of love, abstinence and excess

alike involve but one person; any step in the direction of

sensuality, however, places us in the presence of the Other,

and involves us in the demands and servitudes to which our

choice binds us (except in the case of Diogenes, where both

the limitations and the merits of reasonable expediency are self-

evident). I know no decision which a man makes for simpler

or more inevitable reasons, where the object chosen is weighed

more exactly for its balance of sheer pleasure, or where the

seeker after truth has a better chance to judge the naked

human being. Each time, from a stripping down as absolute as

that of death, and from a humility which surpasses that of

defeat and of prayer, I marvel to see again reforming the

complex web of experiences shared and refused, of mutual

responsibilities, awkward avowals, transparent lies, and pas-

sionate compromises between my pleasures and those of the

Other, so many bonds impossible to break but nevertheless so

quickly loosened. That mysterious play which extends from

love of a body to love of an entire person has seemed to me

noble enough to consecrate to it one part of my life. Words

for it are deceiving, since the word for pleasure covers con-

tradictory realities comprising notions of warmth, sweetness,

and intimacy of bodies, but also feelings of violence and agony,

and the sound of a cry. The short and obscene sentence of

Posidonius about the rubbing together of two small pieces of

flesh, which I have seen you copy in your exercise books with

the application of a good schoolboy, does no more to define

the phenomenon of love than the strings touched by the finger

account for the infinite miracle of sounds. Such a dictum is

less an insult to pleasure than to the flesh itself, that amazing

instrument of muscles, blood, and skin, that red-tinged cloud

whose lightning is the soul. VARIUS MULTIPLEX MULTIFORMIS Marullinus, my grandfather, believed in the stars. This tall old man, emaciated and sallow with age, conceded to me much the same degree of affection, without tenderness or visible sign, and almost without words, that he felt for the animals on his farm and for his lands, or for his collection of stones fallen from the sky. He was descended from a line of ancestors long established in Spain, from the period of the Scipios, and was third of our name to bear senatorial rank; before that time our family had belonged to the equestrian order. Under Titus he had taken some modest part in public affairs. Provincial that he was, he had never learned Greek, and he spoke Latin with a harsh Spanish accent which he passed on to me, and for which I was later ridiculed in Rome. His mind, however, was not wholly uncultivated; after his death they found in his house a trunk full of mathematical instruments and books untouched by him for twenty years. He was learned in his way, with a knowledge half scientific, half peasant, that same mixture of narrow prejudice and ancient wisdom which characterized the elder Cato. But Cato was a man of the Roman Senate all his life, and of the war with- Carthage, a true representative of the stern Rome of the Republic. The almost impenetrable hardness of Marullinus came from farther back, and from more ancient times. He was a man of the tribe, the incarnation of a sacred and awe-inspiring world of which I have sometimes found vestiges among our Etruscan soothsayers. He always went bareheaded, as I was criticized for doing later on; his horny feet spurned all use of sandals, and his everyday clothing was hardly distin- guishable from that of the aged beggars, or of the grave tenant farmers whom I used to see squatting in the sun. They said that he was a wizard, and the village folk tried to avoid his glance. But over animals he had singular powers. I have watched his grizzled head approaching cautiously, though in friendly wise, a nest of adders, and before a lizard have seen his gnarled fingers execute a kind of dance. On summer nights he took me with him to study the sky from the top of a barren hill. I used to fall asleep in a furrow, tired out from counting meteors. He would stay sitting, gazing upward and turning imperceptibly with the stars. He must have known the systems of Philolaus and of Hipparchus, and that of Aristarchus of Samos which was my choice in later years, but these speculations had ceased to interest him. For him the stars were fiery points in the heavens, objects akin to the stones and slow-moving insects from which he also drew portents, constituent parts of a magic universe in which were combined the will of the gods, the influence of daemons, and the lot apportioned to men. He had cast my horoscope. One night (I was eleven years old at the time) he came and shook me from my sleep and announced, with the same grumbling laconism that he would have employed to predict a good harvest to his tenants, that I should rule the world. Then, seized with mistrust, he went to fetch a brand from a small fire of root ends kept going to warm us through the colder hours, held it over my hand, and read in my solid, childish palm I know not what confirmation of lines written in the sky. The world for him was all of a piece; a hand served to confirm the stars. His news affected me less than one might think; a child is ready for anything. Later, I imagine, he forgot his own prophecy in that indifference to both present and future which is characteristic of advanced age. They found him one morning in the chestnut woods on the far edge of his domain, dead and already cold, and torn by birds of prey. Before his death he had tried to teach me his art, but with no success; my natural curiosity tended to jump at once to conclusions without burdening itself under the complicated and somewhat repellent details of his science. But the taste for certain dangerous experiments has remained with me, indeed only too much so.

My father, Aelius Hadrianus Afer, was a man weighed down

by his very virtues. His life was passed in the thankless duties

of civil administration; his voice hardly counted in the Senate.

Contrary to usual practice, his governorship of the province of

Africa had not made him richer. At home, in our Spanish

township of Italica, he exhausted himself in the settlement of

local disputes. Without ambitions and without joy, like many

a man who from year to year thus effaces himself more and

more, he had come to put a fanatic application into minor

matters to which he limited himself. My mother settled down, for the rest of her life, to an austere widowhood ; I never saw her again from the day that I set out for Rome, summoned hither by my guardian. My memory of her face, elongated like those of most of our Spanish women and touched with melancholy sweetness, is confirmed by her image in wax on the Wall of Ancestors. She had the dainty feet of the women of Gades, in their close-fitting sandals; the gentle swaying of the hips which marks the dancers of that region was also visible in this virtuous young matron.

At sixteen I returned to Rome after a stretch of preliminary

training in the Seventh Legion, stationed then well into the,

Pyrenees, in a wild region of Spain very different from the

southern part of the peninsula where I had passed my child-

hood. Acilius Attianus, my guardian, thought it good that some

serious study should counterbalance these months of rough

living and violent hunting. He allowed himself, wisely, to be

persuaded by Scaurus to send me to Athens to the sophist

Isaeus, a brilliant man with a special gift for the art of im-

provisation. Athens won me straightway; the somewhat

awkward student, a brooding but ardent youth, had his first

taste of that subtle air, those swift conversations, the strolls in

the long golden evenings, and that incomparable ease in which

both discussions and pleasure are there pursued. Mathematics

and the arts, as parallel studies, engaged me in turn; Athens

afforded me also the good fortune to follow a course in medicine

under Leotichydes. The medical profession would have been

congenial to me; its principles and methods are essentially

the same as those by which I have tried to fulfil my function

as emperor. I developed a passion for this science, which is

too close to man ever to be absolute, but which, though subject

to fad and to error, is constantly corrected by its contact with

the immediate and the nude. Leotichydes approached things

from the most positive and practical point of view; he had

developed an admirable system for reduction of fractures.I was not much liked. There was, in fact, no reason why I should have been. Certain traits, for example my taste for the arts, which went unnoticed in the student at Athens, and which was to be more or less generally accepted in the emperor, were disturbing in the officer and magistrate at his first stage of authority. My Hellenism was cause for amusement, the more so in that ineptly I alternated between dissimulating and display- ing it. The senators referred to me as “the Greekling”. I was beginning to have my legend, that strange flashing reflection made up partly of what we do, and partly of what the public thinks about 11s. Plaintiffs, on learning of my intrigue with a senator’s wife, brazenly sent me their wives in their stead, or their sons when I had flaunted my passion for some young mime. There was a certain pleasure in confounding such folk by my indifference. The sorriest lot of all were those who tried to win me with talk about literature. The technique which I was obliged to develop in those unimportant early posts has served me in later years for my imperial audiences: to give oneself totally to each person throughout the brief duration of a hearing; to reduce the world for a moment to this banker, that veteran, or that widow; to accord to these individuals, each so different though each confined naturally within the narrow limits of a type, all the polite attention which at the best moments one gives to oneself, and to see them, almost every time, make use of this opportunity to swell themselves out like the frog in the fable; and finally to devote seriously a few moments to thinking about their business or their problem. It was again the method of the physician; I uncovered old and festering hatreds, and the leprous sores of lies. Husbands against wives, fathers against children, collateral heirs against everyone: the small respect in which I personally hold the institution of the family has hardly held up under it all. It is not that I despise men. If I did I should have no right, and no reason, to try to govern. I know them to be vain, ignorant, greedy, and timorous, capable of almost anything for the sake of success, or for raising themselves in esteem (even in their own eyes), or simply for avoidance of suffering. I know, for I am like them, at least from time to time, or could have been. Between another and myself the differences which I can recognize are too slight to count for much in the final total; I try therefore to maintain a position as far removed from the cold superiority of the philosopher as from the arro- gance of a ruling Caesar. The most benighted of men are not without some glimmerings of the divine: that murderer plays passing well upon the flute; this overseer flaying the backs of his slaves is perhaps a dutiful son; this simpleton would share with me his last piece of bread. And there are few who cannot be made to learn at least something reasonably well. Our great mistake is to try to exact from each person virtues which he does not possess, and to neglect the cultivation of those which he has. I might apply here to the search for these partial virtues what I was saying earlier, in sensuous terms, about the search for beauty. I have known men infinitely nobler and more perfect than myself, like your father Antoninus, and have come across many a hero, and even a few sages. In most men I have found little consistency in adhering to the good, but no steadier adherence to evil; their mistrust and indiffer- ence, usually more or less hostile, gave way almost too soon, almost in shame, changing too readily into gratitude and respect, which in turn were equally short-lived; even their selfishness could be bent to useful ends. I am always surprised that so few have hated me; I have had only one or two bitter enemies, for whom I was, as is always the case, in part responsible. Some few have loved me: they have given me far more that I had the right to demand, or to hope for: their deaths, and sometimes their lives. And the god whom they bear within them is often revealed when they die.

Had it been too greatly prolonged, this life in Rome would

undoubtedly have embittered or corrupted me, or else would

have worn me out. My return to the army saved me. Army

life has its compromises too, but they are simpler. Departure

this time meant travel, and I set out with exultation. I had

been advanced to the rank of tribune in the Second Legion

Adjutrix, and passed some months of a rainy autumn on the

banks of the Upper Danube with no other companion than

a newly published volume of Plutarch. In November I was

transferred to the Fifth Legion Macedonica, stationed at that

time (as it still is) at the mouth of the same river, on the frontiers

of Lower Moesia. Snow blocked the roads and kept me from

travelling by land. I embarked at Pola, but had barely time on

the way to revisit Athens, where later I was so long to reside.

News of the assassination of Domitian, announced a few days

after my arrival in camp, surprised no one, and was cause for

general rejoicing. Trajan was promptly adopted by Nerva;

the advanced age of the new ruler made actual succession a

matter of months at the most. The policy of conquest on

which it was known that my cousin proposed to launch Rome,

the regrouping of troops which began, and the progressive

tightening of discipline, all served to keep the army in a state

of excited expectancy. Those Danubian legions functioned

with the precision of newly greased military machines; they

bore no resemblance to the sleepy garrisons which I had known

in Spain. Still more important, the army’s attention had ceased

to centre upon palace quarrels and was turned instead to the

empire’s external affairs; our troops no longer behaved like a

band of lictors ready to acclaim or to murder no matter

whom. Trajan was in command of the troops in Lower Germany;

the army of the Danube sent me there to convey its felicitations

to him as the new heir to the empire. I was three days’ march

from Cologne, in mid-Gaul, when at the evening halt the death

of Nerva was announced. I was tempted to push on ahead of

the imperial post, and to be the first to bring to my cousin the

news of his accession. I set off at a gallop and continued with-

out stop, except at Treves where my brother-in-law Servianus

resided in his capacity as governor. We supped together. The

feeble head of Servianus was full of imperial vapours. This

tortuous man, who sought to harm me or at least to prevent

me from pleasing, thought to forestall me by sending his own

courier to Trajan. Two hours later I was attacked at the ford

of a river; the assailants wounded my orderly and killed our

horses. We managed, however, to lay hold of one of the attack-

ing party, a former slave of my brother-in-law, who told the

whole story. Servianus ought to have realized that a resolute

man is not so easily turned from his course, at least not by any

means short of murder, but before such an act his cowardice

recoiled. I had to cover some three miles on foot before coming

upon a peasant who sold me his horse. I reached Cologne

that night, beating my brother-in-law’s courier by only a few

lengths. This kind of adventure met with success; I was the

better received for it by the army. The emperor retained me

there with him as tribune in the Second Legion Fidelis. That fact was apparent when the empress thought to advance my career in arranging for me a marriage with his grand-niece. Trajan opposed himself obstinately

to the project, adducing my lack of domestic virtues, the extreme youth of the girl, and even the old story of my debts. The empress persisted with like stubbornness ; I warmed to the game myself; Sabina, at that age, was not wholly without charm. This marriage, though tempered by almost continuous absence, became for me subsequently a source of such irritation and annoyance that it is hard now to recall it as a triumph at the time for an ambitious young man of twenty-eight. ....

I was reproached at this period for adulterous relations with women of high rank. Two or three of these much criticized liaisons endured more or less up to the beginning of my princi- pate. Although Rome is rather indulgent toward debauchery, it has never favoured the loves of its rulers. Mark Antony and Titus had a taste of this. My adventures were more modest than theirs, but I fail to see how, according to our customs, a man who could never stomach courtesans and who was already bored to death with marriage might otherwise have come to know the varied world of women. My elderly brother-in-law, the impossible Servianus, whose thirty years’ seniority allowed him to stand over me both as schoolmaster and spy, led my enemies in giving out that ambition and curiosity played a greater part in these affairs than love itself; that intimacy with the wives introduced me gradually into the political secrets of the husbands, and that the confidences of my mistresses were as valuable to me as the police reports with which I regaled myself in later years. It is true that each attachment of any duration did procure for me, almost inevitably, the friendship of the fat or feeble husband, a pompous or timid fellow, and usually blind, but I seldom gained pleasure from such a con- nection, and profited even less. I must admit that certain indiscreet stories whispered in my ear by my mistresses served to awaken in me some sympathy for these much mocked arid little understood spouses. Such liaisons, agreeable when the women were expert in love, became truly moving when these women were beautiful.

The war lasted eleven months, and was atrocious. I still believe the annihilation of the Dacians to have been almost justified; no chief of state can willingly assent to the present of an organized enemy established at his very gates. But the

collapse of the kingdom of Decebalus had created a void in those regions upon which the Sarmatians swooped down; bands starting up from no one knew where infested a country already devastated by years of war and burned time and again by us, thus affording no base for our troops, whose numbers were in any case inadequate; new enemies teemed like worms in the corpse of our Dacian victories. Our recent successes had sapped our discipline: at the advance posts I found some- thing of the gross heedlessness evinced in the feasting at Rome. Certain tribunes gave proof of foolish over-confidence in the face of danger: perilously isolated in a region where the only part we knew well was our former frontier, they were depending for continued victories upon our armament, which I knew to be daily diminishing from loss and from wear, and upon reinforcements which I had no hope to see, knowing that all our resources would thereafter be concentrated upon Asia. Another danger began to threaten: four years of official requisitioning had ruined the villages to our rear; from the time of the first Dacian campaigns, for each herd of oxen or flock of sheep so ostentatiously captured from the enemy I had seen innumerable droves of cattle seized from the inhabitants.

Gracias por la reseña. Lo tendré en cuenta. Estas muy linda. Te mando un beso.

ReplyDeleteGracias por the comment:)

DeleteWhat a beautiful place to be reading! It does sound like an interesting reading. A slice of life of the turmoil's of an artist. thanks so much! Love this outfit, perfect to be sunning in.

ReplyDeleteIt was an interesting reading for sure.

DeleteAdoring your outfit and this location where you are bringing your hearty review from. Thanks for giving us so much information about this memoir. I'm sure now days he might be on at least 2 antidepressants and wouldn't be able to write a word. Thanks for the lovely post. All the best to a delightful July!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much. :)

DeleteBoa tarde, excelente domingo e um bom início de semana. Parabéns pela dica e maravilhosa , explicações.

ReplyDeleteobrigada

DeleteI haven't read anything by Marguerite Yourcenar since my school days. Visiting the Marguerite Yourcenar museum and park bearing her name just over the border in France has long been on my list, as it's not far from our September holiday address. Perhaps this year ... xxx

ReplyDeleteOh, visiting her museum sounds delightful! I hope you'll get the chance to do it.

DeleteA long letter written to Marcus Aurelius certainly is a fresh and original format for a book. Looks like you'r enjoying summer in Buna.

ReplyDeleteI'm enjoying my summer, thank you. Alternating between working and resting.

DeleteSounds really good. Thanks for the book review! Here, in Turkey, her "Coup de Grace" book is very popular but ı havent read it yet. Have a wonderful July and summer, Greetings.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate the recommendation. I will look it up!

DeleteYou're wearing your beautiful cherry dress on that terrace that looks so relaxing for a read! As I said, I'm going to have to read that book! Thank you for letting me know about this masterpiece!

ReplyDeleteThis is a terrace of hotel Buna. It's wonderful!

Delete